"No Water, No Development?" No Thinking Here.

If things go according to plan, tomorrow's LA Times letters section will carry a brief letter from me responding to an LAT editorial that ran last weekend, No Water, No Development.

If things go according to plan, tomorrow's LA Times letters section will carry a brief letter from me responding to an LAT editorial that ran last weekend, No Water, No Development.Because letters to the editor are necessarily brief, I decided to spend some time today to do a more complete fisking of the editorial -- even though many of my readers may not find this overly interesting. I do because my business handles public affairs assignments for land developers and water districts.

As background, supplying enough water to all the folks who like calling SoCal home has always been a dicey affair at best, and it's getting worse.

As background, supplying enough water to all the folks who like calling SoCal home has always been a dicey affair at best, and it's getting worse.- California's population is growing fast -- it's expected to grow from its current 28 million to 38 million by 2030 -- and more mouths need more water.

- There's been a prolonged drought in the Colorado River basin, along with a lot of growth in Arizona, and that's put pressure on our Colorado River resources.

- The Sierra snowpack's about average this year, but this is the first time in a few years that it has been, so that supply source is not too reliable.

- Aquifers need replenishment they tend not to get in dry years, so they're getting over-drawn.

- Global warming advocates read their

tea leavescomputer models and forecast hotter, drier weather for SoCal.

Walley: "But what about those people who are suffering during this change?"

Suckling: "As I say, it is not a simple thing. We have entire communities that have grown up in this system of land-based government subsides. To change that is not a painless thing."

Walley: "You, are creating rural refugees!"

Kieran's ego finally shows, his speech picks up speed and emphasis: "It's more than rural. I'm dealing with the Grand Canyon, Hoover Dam and Los Angeles. Thirteen million people are used to getting their water this way, I say that's great, but we are going to show them a different way to do it!"

Walley: "You are forcing change on society and you are aware of it?"

Suckling: "Yeah! Isn't that what an activist is! What do you think an activist is? We change society!"

Walley: "Can't you do this in a humane and gentle way?"

Suckling: "It is sad, but I don't hear you put that in a direct relationship to the effect on the land. I hear you talk about the pain of the people but I don't see you match that up with the pain of the species."

Walley (dumbfounded): "What?"

Suckling: "A loach minnow is more important, than say, Betty and Jim's ranch-a thousand times more important. I'm not against ranching, it is a job. My concern is the impact on the land."

A loach minnow is a thousand times more important than Betty and Jim's ranch -- not the loach minnow species, but a single loach minnow.

A loach minnow is a thousand times more important than Betty and Jim's ranch -- not the loach minnow species, but a single loach minnow.Backing up this extreme belief with litigation, the Center used the Endangered Species Act to sue to stop the pumps that bring water to SoCal from the San Joaquin/Sacramento Delta, our primary water source. They triumphed, and the result is a 30% reduction in the amount of water coming from NoCal to SoCal.

The fix is a re-tooling of the Delta, which it needs if it is going to survive its current ecologically tenuous condition. Combined with that would be a canal that would bring water south without impacting the Delta -- a proposition the Greenies are fighting tooth and nail, natch.

Against that background, the LAT opined that because water is in short supply, development should stop in the suburbs.

During the 20th century in Southern California, city founders made a religion out of building bounteous -- and sometimes boundless -- suburbs in the most unlikely locations. They assumed that the water their new communities needed to thrive would somehow flow to them.

For the most part, if they made their claim early enough, they were right. Because the state and federal governments poured billions of dollars into dam and canal systems that carried water over vast distances, past far-flung burgs, engineers could almost always find a way to get a little more of it to thirsty towns. In tract after tract, water followed development, rather than the other way around.

Left unsaid in this little history lesson is that there was no greater champion of these programs than one Harry Chandler, the publisher of a little rag called The Los Angeles Times. He had the good sense to realize that if he was ever going to have a world class media empire, he was going to have to get water to LA.

Left unsaid in this little history lesson is that there was no greater champion of these programs than one Harry Chandler, the publisher of a little rag called The Los Angeles Times. He had the good sense to realize that if he was ever going to have a world class media empire, he was going to have to get water to LA.In the 21st century, this ethos of expansion must come to an end. ...The statement is absurd. If we are to follow the water, then all of the development in California would be along the northern coast, in the northern Central Valley, and in the Sierras -- all of which are sparsely populated.

It's a matter of common sense: It is time for development in California to follow the water. Even as our state continues to grow, sprawl can no longer be our birthright. Hydrologically remote regions cannot depend on new sources of imported water for human needs, much less for verdant lawns.

"Follow the water" is an utterly ridiculous concept also because we have the capacity and infrastructure to move water. Any development that is near existing water infrastructure -- say the city of LA in its semi-arid desert environment -- is as well situated, if not better situated, than one along a natural water source.

Calling for an end to suburban development to fix our water problems is no more a solution than would be a call to have the clouds drop more rain. Neither is realistic.

The LAT then goes through a three-paragraph exercise in diminishing the consequence of environmental and anti-growth laws it lobbied hard for itself. Thanks in part to the LAT's support, we now have laws in CA that require new development to prove that there is a 20-year supply of water sufficient to meet the community's dry weather demand.

This water can't be "paper water," i.e., contracts for water that isn't there; it must be provable as real water that isn't committed elsewhere. Yet the LAT forgets what it lobbied for:

Individual water districts generate the estimates. And some of these districts, in preparing reports for land-use planners, may rely too heavily on "paper water," flows that exist in legal allocations but aren't really on hand and may never be. As one former state legislator explains, "If people point to paper water, there's always enough for everybody."But that's already been litigated, and the case law says the water has to be real. Water districts know this and know they will be sued if they allow development for which there isn't sufficient water, so they're serious about their water management plans.

Still, the LAT is negative:

Put bluntly, it makes little sense to depend on new water imports -- even if they "exist" as allocations -- when planning thousands of new homes in an isolated region. But depending instead on more secure local water supplies -- responsibly managed groundwater, gains from conservation, wastewater recycling and reuse -- is anomalous to California culture and will be a hard sell.It is correct that relying on the Colorado River aqueduct and the State Water Project for new water imports isn't wise; the Hell has been allocated and litigated out of that water.

But what is this about responsibly managed groundwater, conservation and recycled water being a hard sell? The LAT simply does not know what it's writing about; it's making things up to create dread instead of optimism.

The dread comes from a fundamentally negative view of authority, which is pretty much a prerequisite for being an editorial writer.

Critics of building-friendly local governments frequently complain that water and land-use officials are controlled by developers, who have long been enthusiastic contributors to political campaigns. Whether that is true or not, it's almost certainly the case that California water agency culture is loath to say no to developers for a less-pernicious reason: Water districts are in the business of delivering water to local communities -- they don't see their job as determining water use policy -- and they don't like to say no to their customers.If developers are so powerful, how come the homebuilding industry is one of the most heavily regulated in the country? When I speak on the subject, I usually start with the line, "Did you know it's easier in California to get permission to cut open someone's chest and stick a new heart in there than it is to get permission to build a house?"

Builders' whims are summarily crushed by the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the environmental quality acts of the federal government and various state governments, and regulations that require no runoff to leave construction sites, no grading during bird nesting season, no construction noise near nesting birds, strict building limits in fire zones, and that they fund roads, parks and schools.

Clearly, the idea that developers buy influence has plenty of proof against it and precious little for it.

And as for water districts, their mission is to provide a reliable source of safe water and an environmentally sound treatment of wastewater; it is not to grow. They have done wondrous things to account for growth, applying specialized engineering expertise creatively to bring water to people who need it, and to conserve it as much as possible.

In district after district throughout California, an emphasis on conservation and water recycling has allowed them to meet growing demand with the same amount of water. That goes for LA too, by the way.

But the LAT thinks it's all a wasteful game, especially when it comes to how the editorial writer thinks we should live; not with the suburbs' safety, cleanliness and recreation, but as the editorial writer him/herself no doubt lives, in a dirty and dour urban setting that oozes with "more green than you" snottiness. (More in a bit on why that's false snottiness.)

The editorial wants us to "follow the water" to these environments, shunning the suburbs because they have, horror of horrors!, lawns.

The editorial wants us to "follow the water" to these environments, shunning the suburbs because they have, horror of horrors!, lawns.Even as our state continues to grow, sprawl can no longer be our birthright. Hydrologically remote regions cannot depend on new sources of imported water for human needs, much less for verdant lawns.What silliness. First, there is no development in hydrologically remote regions. If there's an aqueduct or pipeline serving an area, it's not hydrologically remote. That goes for downtown LA, which steal its water from the Owens Valley and pipes it down to what was a rather hydrologically remote area.

Second, let's look at what's going on with those "verdant lawns."

First, of course, they get played on and lived on, and they help diminish the asphalt heat island effect of the city. But more than that, they are watered in ways the LAT feels is a "hard sell," but is not.

California’s water providers and community developers are far ahead of the Times in recognizing the water shortage and creating solutions, and many of these solutions focus on landscape irrigation. In fact, solutions the Times refers to as “potential” already exist, thanks to the cooperative efforts of water districts and land developers.

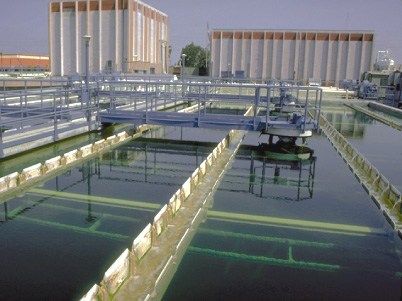

For example, we helped win approvals for a new planned community that tripled the size of the town of Calimesa, on the eastern edge of the LA metropolis. The developer worked with the local water district to receive permitting for a water recycling plant that will deliver reclaimed water to the front yards of homes, where it will be used for irrigation.

In South Orange County, both the Irvine Ranch Water District and Santa Margarita Water District (the county’s largest and second largest) have been recycling water and using it for irrigation since the 1970s. At IRWD for example, recycled water:

In South Orange County, both the Irvine Ranch Water District and Santa Margarita Water District (the county’s largest and second largest) have been recycling water and using it for irrigation since the 1970s. At IRWD for example, recycled water:- Irrigates 5,650 acres of parks, golf courses, school playfields, athletic fields, and many common areas,

- Irrigates over 1,000 acres of crops,

- Is used in industry, where one application at a carpet mill saves 500,000 to one million gallons of drinking water per day,

- And now is being introduced into office buildings for toilet flushing.

Innovation like this is happening all over California. Districts in the Central Valley with brackish groundwater are putting in desalters. Orange County just launched a toilet-to-tap program which required no "hard sell" to area residents because it's safe and will protect our aquifer. And on and on.

To the LAT, this innovation appears to be a thing of the future, something speculative, something not to be counted on. They would rather mandate how we live:

Californians' devotion to the easy suburban lifestyle (or at least, the easy suburban lifestyle as we know it). Thirty-nine percent of residential water use in California occurs outdoors, mainly when homeowners water their lawns. One way to secure "additional" water for growth is to cut yard sizes and impose landscaping restrictions on new and existing neighborhoods.Apparently the LAT hasn't toured a model complex lately and seen the small yards, the common areas landscaped in drought-tolerant plants, and the sophisticated irrigation systems that measure ground moisture and only water as necessary.

No new regulations are required to accomplish this. Land prices have forced the private sector to respond with smaller yards, the environmental review process brings in water conservation methodologies, and the regional water quality control board mandates runoff controls, so landscape is irrigated sparingly.

But the LAT knows none of this. The editorial writer sits in downtown LA, surrounded by concrete and asphalt, and thinks the worse, as he/she should, because the environment there is the worst. Buildings are stuffed with inefficient toilets and fixtures. There is no runoff control. There is no recycled water. There is no toilet to tap program. There is infrastructure that's undersized and in need of major upgrading -- and we're supposed to move there?

Surrounded by the urban stupidity that is LA, the writer lashes out at the suburbs in some sort of tribal battle of urbanites against suburbanites. Sorry, though; we're not picking up this club because there's a better, two-fold solution.

First, we need to address the infrastructure issue with bonds that will fix the Delta and provide new conveyance and storage systems. Second, we must continue to let people choose where they wish to live, and let water districts and developers respond to existing conditions and regulations with ever more innovative approaches to acquiring and conserving water.

Just because the LAT says we need a state-controlled system that subjugates free will to the whims of urbanists doesn't mean we have to be so thick-headed and so uninnovative as to follow them.

Labels: Conservation, Development, LA Times, Water

<< Home